World View

The following discussion looks at several implications of the gold rushes in the 1850s. The implications are both local and world wide and are included, not only for interest, but because this knowledge undoubtedly affected the miners at the time and their subsequent attitudes to their station in life and their future in this class conscious society of the time.

Payable gold was discovered and registered in NSW in February 1851 and in Victoria in June 1851. Thousands of people rushing to the goldfields was the immediate result. This posed a problem for the agricultural industry as they rapidly lost workers. A similar problem had occurred to farmers in the 1840s in NSW, Victoria and the area that was to become Queensland, due to the cessation of the transport of convicts to these areas in Australia.

As the Crown owned all the gold in the ground, it was realised, by June 1851, that the government needed to assert control. This was effected through licensing which would keep a semblance of control over the miners and give the government extra revenue which could be used to develop roads and bridges, increase the police force and local militia and improve charities, and educational and scientific institutions. At a fee of 30s per month for 5000 licenses, revenue of £90 000 pa was gained. 1Sydney Morning Herald, 5 June 1851.

It was also realised that our population would increase significantly, attracting gold seekers from overseas. Whilst this would increase the revenue from gold, and increase our exports, it would also increase demand for food and accommodation, which would, in turn, result in increased prices. Farmers needed labour to increase their production and take advantage of the higher demand for goods. But they would no longer be able to attract workers by paying £25 per year. The government tried to help the farmers by charging this high fee for the gold license, thinking that farm labourers could not afford this money. In Victoria protest against these high fees led to the Eureka Stockade. There was initially much objection to the fee in the Bathurst and Orange, where the earliest rush to gold began NSW in February 1851. Many left the fields, presumably going back to their previous occupation. Many were going to refuse to pay the fee. At Ophir two Commissioners and 18 mounted troopers were needed to enforce the tax. The general feeling appeared to be in favour of thirty shillings a cradle, which being worked mostly by four or five men would amount to something like 5s. to 7s. 6d. a head per month. 2Freeman’s Journal, 12 June 1851. Mining without a license meant expulsion from the claim and confiscation of any gold in that miner’s possession. From newspaper reports it was thought that the government in NSW was concerned that any unrest on the goldfields here might result in rebellion, as it did in Victoria, and so they did try to moderate rules and regulations to ease their impact. For example, within a short period of time, it was reported that the miners acquiesced peacefully to the license fee, especially when the Commissioner, in the absence of money, was prepared to take half an ounce of gold for the license or allow a week to raise the money.

However the cost of the license was not the only problem facing hopeful miners. Miners needed special skills and patience to recover the gold in difficult situations, especially the steep and dangerous land in Upper Araluen and Bell’s Creek.3(now Bells Creek – in 2018 the NSW naming policy removed the apostrophe in place names. This was to allow rapid retrieval of place names from emergency services databases.) As the saying goes, the best shepherds will make but very indifferent miners and within a very short period of time it was noted that …

The diurnal stream of population from the metropolis flows on steadily. Lines of loaded teams and carts surrounded by foot passengers are continually passing through the town [Ophir]. One feature we have noticed during the few days last past, the sojourners to the mines appears to be of a much better class than those who preceded them, most of them apparently being provided with all the requisites for an encampment, as well as working implements. Judging by externals we should imagine them to consist in great part of respectable trades men, mechanics, and amongst the rest of a few compositors. 4Ibid.

Another problem which not only affected Australia but also Britain and Europe was supply and demand for gold. Gold from both the Californian gold rush (1848 – 1855) and gold from Australia was sold to England. For a time this extra supply was absorbed by England’s commercial operations. But in Holland, Belgium and France the extra supply of gold from their colonies was causing problems. By 1850 the amount of gold produced in the world had increased ten times from that produced in 1840. 5https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/1982/01/1982a_bpea_cooper_dornbusch_hall.pdf. This lead to a decline in the value of gold and a decline in the value of the gold sovereign. The extra availability of gold from Australia in the 1850s continued this decreasing trend. The gold sovereign did not represent as much labour or produce due to its declining value. Consequently the price of consumables, including food, increased in value. This also became a problem in Britain and in Europe. Thus the increasing price of consumables in NSW was further impacted by this world wide problem. During this decade, the world production of silver only increased by 10 per cent. Holland’s answer to the decreased value of gold was to change from a gold standard to a silver standard and the demand for silver increased leading to an increase in its value. Other countries did not follow Holland but they hoped that bimetallism was better at stabilizing prices than a regime based on only one currency metal, as supply shocks to gold and silver partially offset one another. But for this system to work, international co-operation was needed. Thus the gold standard was adopted again in the 1870s.

In August 1851 there were new regulations for gold seekers in NSW. 6Empire, 7 August 1851. Licenses were now only for alluvial gold, not gold in the matrix. This matrix gold was to be charged with a royalty of 10 percent if found on crown land and five per cent if found on private property. The fund from gold licenses was to be augmented by the recovery of matrix gold. The mining of this gold requires much greater expenditure on heavy equipment and usually only occurs when the alluvial gold is mined out. Failure to obtain a license resulted in seizure of gold and prosecution. Opposition to this expense was that payment for the license was required even though gold may not be found.

Also in August 1851 an example was made of Dr Kerr, a license defaulter. 7Peoples Advocate and NSW Vindicator, 9 August 1851. Dr Kerr mined for gold on the Meroo Creek/Louisa Creek waterways, 22 miles south of Mudgee. He had no license and allegedly 100 dwt of his gold was confiscated. 100 dwt = 1720oz. At £3.14.00 per ounce this is equal to £6364.

Another consequence of not having a license occurred at Oakey Creek on the Turon field near Lithgow in September 1851 – that of cradle smashing. 8Bathurst Free Press and Mining Journal, 17 September 1851. The police visited the field to inspect licenses and one policeman entered a tent that was only occupied by a cradle, the owner being absent. The cradle was taken outside and smashed. The paper did not report any consequences for this action but we can guarantee that it did not engender any sympathy towards the police and towards licensing.

In October 1851 there were further regulations. 9Goulburn Herald and County of Argyle Advertiser, 11 October 1851. Anyone occupying any portion of a gold field, not necessarily a miner, was to pay the license fee. The size of the claim for alluvial gold was charged and the fee for alluvial working on private land was to be half that for Crown lands. Miners working matrix gold were subject to strict rules and expensive fees, a bond of £2000 and a Royalty of 10 per cent. For any failure to follow rules, their claim would be forfeited. Rules also governed waterholes. The rules for alluvial gold were acceptable to miners, but those for matrix gold were most unpopular. 10Sydney Morning Herald, 20 October 1851. Hence some modifications occurred, 11The People’s Advocate and the NSW Vindicator, 29 November 1851. but arguments continued and adjustments to the rules throughout 1852 and again new regulations introduced in February 1853. 12Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, 9 February 1853. These 64 regulations covered all aspects of gold mining and associated businesses and applied to all goldfields including those in the Braidwood District.

The regulations about matrix gold did not affect the Araluen Valley in 1853 as the miners here were mining alluvial gold only. Perhaps this disaffection amongst the miners in the Orange/Bathurst area resulted in the large number that came to Araluen and were prepared to endure the extreme hardships encountered in our valley. 13For a discussion on these hardships see the articles on the fields in the Araluen Valley on this site..

Gold Mining in the Araluen Valley in the 1850s and 1860s

Much of the following account of gold in the Araluen Valley is from newspapers and from books written by Barry McGowan. 14McGowan, Barry The Golden South, Canberra Fine Print, 2000.

McGowan, Barry Dust and Dreams, University of NSW Press Ltd. 2010

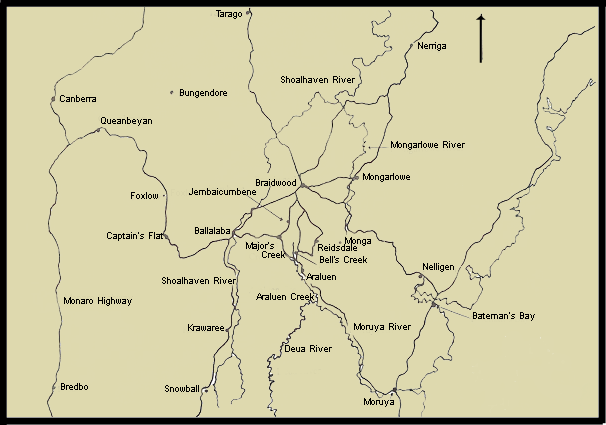

General Location Map

From Barry McGowan, The Golden South

McGowan’s book divides the Araluen goldfields into three large areas:

- Upper Araluen includes the source of Araluen Creek, Deep Creek, Apple Tree Flat, and the Dirty Butter Creek area of North Araluen.

- Middle Araluen includes the main area of settlement – Araluen, Burketown, Newtown and Redbank.

- Lower Araluen includes Clear Hills, Crown Flat, Mudmelong, and Favourite Flat.

The Araluen workings became the most permanent in NSW at the time, with gold being scattered in paying quantities throughout the entire valley.

In September 1851 gold was found near the estuary of the Moruya River. The deposits were traced upstream to the junction with Araluen Creek. Initially there were only 50 to 100 diggers in this area, finding up to 6ozs in a week. Gold was valued at £3.13s per oz. in the 1850s. 15https://sydneylivingmuseums.com.au/stories/what-happened-if-goldminer-found-gold By the end of the month the average return was 1.5 to 2ozs per week per man. By then about a 100 miners were working at the upper diggings and 150 at the lower diggings. There were no published reports of gambling or sly grog selling. 16Goulburn Herald. 20.9.1851.

By late October 1851 the number of miners were increasing daily, many from Sydney by land and by sea, initially to Nelligen. Mining was from the Bell’s Creek Falls, and down the valley for about 8 km. 17McGowan, The Golden South, page 34. It took three months, with a bullock team, to come from Sydney to Braidwood. There were no roads in those days, only bush tracks, and you had to get along as best you could. There were no bridges to span the rivers or the creeks, and when you came to a creek or river if it was at all swollen by the rains, then you had to camp until the waters subsided. 18Kennedy, Richard Braidwood Dispatch and Mining Journal, Saturday 10 August 1907.

Coming from Sydney or places further afield it was quicker to reach these goldfields by boat. The boats came to the Mullenderry (now Mullenderree) landing on the Moruya River. Mullenderry was on the north bank of the river on the flats beside today’s Princess Highway. The local First Nations people occupied this area at the time.

If you came by boat, travelling the 35 miles from Moruya was difficult as luggage could only be carried on pack horses. The cartage for packing was £3 for one horse, £7 for two horses, for a distance of 35 miles. This would take about 12 hours. The carriers would only take clothing. Provisions and equipment had to be carried by the new arrivals which would take at least four days on foot.

An interesting but very long account of the Araluen diggings was given by G.K in the Sydney Morning Herald.19Sydney Morning Herald, 4 November 1851. Briefly, he saw the first diggers about four miles down the Deua from the Araluen plain. He said that the once beautiful clear stream, resembled the gutters in Sydney during a heavy shower from the action of the cradles. At Mr Badgery’s station, Clear Hills, the diggers can have their horses put in a good grassed paddock, at a charge 2s. per head per week. On the Araluen Plain diggers met the dairyman, Mr. Flanagan, who sold salt, fresh butter and bacon at 1s. per lb. He would also deliver his goods to the miners twice a week at the same price. The miners could give him fresh orders for their next delivery. Flour could be procured at from 35s. to 40s., per cwt., salt beef, 3d., fresh, 2d., mutton, 3d. per lb., tea, from 4s. to 6s. per lb., sugar, 7d., colonial tobacco, 6s butter, 1s. per lb. He noted that there was now only about twenty cradles at work at the two above mentioned diggings, the miners having been disheartened in consequence of not being able to keep the water from flowing into their claim.

Initially all mining was on the alluvial gold, which was much easier to gain and did not require special skills nor the expense of machinery. This gold was found in the top soil, underneath the grass. Mining was relatively easy. Pans and cradles were used near the creeks, but further from the creeks water races had to be dug so the gold could be washed from the sand, silt and small pebbles.

Gold Mining Technology of the 1850s and 1860s

Mining alluvial gold in shallow soils only required simple tools: the gold pan, cradle, sluice box, long tom and a water race. The deep alluvial soils on the Araluen plains required tunnel building knowledge. Dredges were needed to mine gold from the creek beds from the 1870s.

The Gold Pan

This is the simplest way to wash and separate small amounts of alluvium. It is successful as gold is heavier than the silt. Swirling the alluvium in the pan with water will settle the gold. The top alluvium can be carefully swilled away, leaving the gold in the bottom of the pan.

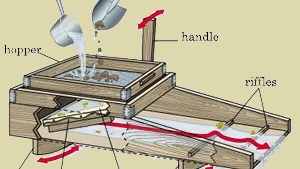

The Gold Cradle

Cradles were needed to wash gold in all areas – the plains and the steep slopes. The gold rush began in Australia as the Californian rush was ending. The Americans who came to Australia at the time were able to show our miners how to build and use the cradle.

The alluvial soil was placed into the hopper and water would wash the smaller particles through the sieve floor of the hopper. The handle was used to rock the cradle to expedite the process. The heavier gold would be stopped by the riffles.

Gold cradle. Courtesy of Encyclopedia Brittannica.

The Sluice Box

A sluice is a channel for water that has obstructions or ‘riffles’ along the base. The riffles slow down the flow of water. They could be made with carpet, blanket material and/or moss, and used to trap the finer gold. The trough can be any length. A long tom is a box sluice that can be 10m or longer and is a permanent fixture.

Water Race

A water race is a channel designed to bring water from a stream to where the gold is mined. The source of the channel has to be above the mining area, so the water will flow under gravity. A water race can be many miles long. There were many water races in the Braidwood gold fields – mostly built by the Chinese. The photos below are of parts of the race, on privately owned land, at Mt Elrington.

Photos, Courtesy of Antony Davies

It appears that this race was built in the 1840s, but probably extended by Chinese workers in the 1850s. James O’Brien did further work to it in the late 1860s and there are mentions of it being repaired and cleaned from time to time up to the 1950s. It was still operating in the 1980s but after that it seems to have been decommissioned by ploughing up some of the race further up behind the homestead. Much of the race is just clay, and the areas running through the main property are lined with rocks on the sides with a clay base. It doesn’t hold water well and depends on a significant amount of water flowing through it to remain full. Evidently Mount Creek was dammed and had a gate about three kilometers up the creek behind the house, and this would have directed a significant quantity of water through the race. Some sections around the house have been covered over with wooden sleepers and some left open. It’s an ingenious piece of work and remarkable that the levels were met to allow a steady flow downhill over such a great distance 20Information from Antony Davies’ research.

A comprehensive article on alluvial mining and tunnelling technology on the Araluen plain was explained in Random Notes from a Wandering Reporter in the 21Sydney Morning Herald, 17 July 1865. …

The mode of working the claims is very complete, and is much more systematic than on any other gold fields in the colony. In fact, were it not so, it is doubtful whether the work would pay, for the gold is so distributed over a large, surface, and amongst such a depth of wash-dirt, that it is only by washing a quantity of the dirt that anything like a payable result is secured. The way the parties proceed is this:— They usually form themselves into companies, say of twelve men, that being the ordinary number, working on the co-operative system, every partner working, or finding a man to work for him. Besides these, other men have to be employed, being paid by the copartnery. Having marked out their boundary, they proceed to open a piece of ground about 100 feet square, which is denominated the paddock. This they proceed to ‘strip’ down to the wash dirt, — the stripping consisting of removing all the alluvial soil lying on the drift or wash dirt, in which the gold is found. The whole of this is carted away, either to some old ground already worked out, to some piece of ground known to be worthless, or in default of either of these, on to a portion of the company’s claim. The earth thus carted out soon forms immense mounds, or ‘tips’ as they are technically termed, from the tip-carts used. It is thus an object to get a place for disposing of the soil, or a ‘ tip ‘ as handy to the work as possible, so as to have as short a lead for the horses as can be obtained. The depth of the cuttings ranges from 25 feet to 35 feet ; the ordinary depth being about 30 feet. The stripping is done by day, and the washing by night, enough being generally stripped in the day to furnish the night’s washing. Thus the hired men work during the day, and the members of the co-partnery at night ; thus keeping an eye on the more important operation of washing. An inclined road is left by which the earth is carted out of the hole that is very quickly made, and after the first few days’ washing, the thing becomes easier, as there is then vacant ground upon which much of the surface soil may be cast.

In one of the large paddocks such as I have described there are usually twenty-five men employed in stripping and filling the carts, one man at the tip to tip the carts, and twelve at the wash-box, six by day and six by night when the claim is in full work— some of the claims working two boxes, when, of course, double the number of men are employed. The larger claims have also twenty five horses at work, carting, the ordinary number being about fourteen horses. To drive these, there are usually three boys employed, and in this a great deal of economy of labour is shown, very much depending upon the horse himself. There is usually one road out of the paddock ‘with the loaded cart, and another into it with the empty vehicle after it has been tipped. The three boys are so placed along the line to and from the tips as to be within a short distance of the horses either going or coming, and to speak to and hurry on any that may lag on the way, or force on others that may stop. This, however, is seldom necessary, for the horses get so perfectly well acquainted with the work required of them that they go of their own accord to the tip, and back to it ready for the man to tilt the cart, returning, and of themselves taking up a position suitable for loading. Nay, more than this, the moment the man sings out ‘ Joe-time,’ which is the Araluen term for ‘spell-oh’ the horses at once stop and look round for the nosebag. A rather amusing incident, exemplifying the peculiar sagacity of these animals, occurred whilst I was at Araluen. One of the horses employed in carting was wanted for some other purpose, and he was led on one side and taken out of the cart. The moment the other horses saw this, they at once ran down together to the spot, breaking their line of march in the most disorderly manner, under the impression that some additional Joe-time had been allowed.

Besides the men, boys, and horses above enumerated, there is an engine employed to keep down the water in the different paddocks. One engine is usually so placed as to be able to pump for two paddocks. The water thus raised is carried into the sluice-boxes, and enables the company to wash their dirt. The engines are kept working night and day, so that the paddocks are kept tolerably dry. There are in all eighteen engines on the ground, all with tubular boilers, and some of them with all the latest improvements. One in particular I admired as being one of the prettiest engines I have seen for a long time, being a 15 h.p. engine, the property of Mr. Blatchford, and working a centrifugal pump. Besides this, there is one engine of 12 h.p., one of 10 h.p., and the rest of 8 and 6 h.p. They not only do the pumping, but they have each each of them a table and circular saw attached, so as to do whatever sawing may be necessary for slabbing wells, or drives, or anything else where support is necessary. Sometimes the engines are hired, and sometimes they are taken to represent one or two shares in the copartnery — usually two shares. . .

There is a run or lead of gold through the length of the valley. The course it has taken is as usual with such leads — a circuitous and eccentric one — though on looking at the ground, one may pretty fairly judge of the line it would be likely to take from the various points of the ranges that would most probably turn the stream, form eddies, or divert the course of the water. The width of the lead of wash-dirt ranges from 100 feet to 150 feet, the depth being from three to five feet. The smaller depth contains a larger proportion of gold than the greater depth, but not so much larger as to make the three-foot stuff more profitable to work. On the contrary, the claim holders would sooner see the deeper than the shallower depth, as a greater quantity of gold is obtained for the superficial surface from the former than from the latter. The cost of opening a paddock such as I have described, if about 100 feet square, will be about £100 per week for ten or twelve weeks. Rather a large outlay you will say, especially as a great portion of it has to be incurred before there is any complete assurance of success or failure. It is no joke, let me tell you, to open, a duffer paddock on Araluen, and yet some thousands of pounds have been expended in this manner.

What makes the expense heavier than it otherwise would be is the cost of labour, which is higher here than elsewhere in the colony ; and has been arbitrarily fixed by the men, who, by a systematic combination, have managed to keep it up ; and by intimidation, and in some cases by violence, have prevented others from working at lower rates. The wages of all men working in the paddock are ten shillings a day, Those who work in drives get sixty five shillings per week. Engine drivers get eighty shillings per week, and boys to drive thirty-five shillings per week. For these wages they work ten hours, divided into four joe times or resting times, for meals, &cc. Time is very punctually kept, and if a man does not get back to his work sharp up to time, he is knocked off from work for that joe, or if he works is not paid for the quarter day. If they are well paid, the men certainly work very hard, and anything like scheming, or an attempt to shuffle out of a fair share of the labour is at once remarked by the men themselves, as well as by the ganger, and if one warning is not sufficient the man gets sent a drift.

For some months past, the yield of gold from Araluen has averaged fully 1200 ounces ; and, as the wash dirt has been pretty uniform in the quantity of gold it has returned, it is to be expected that, unless some such disastrous flood occurs as that which a few years ago devastated the valley, and overwhelmed works and machinery in on general ruin, this yield will be kept up for the next two or three years, by which time the lead through the valley will have been worked out. No deposit of any importance has been found beyond the main stream of wash dirt, although occasional patches probably deposited by eddies or currents, out of the main lead have been hit upon, and have in some instances led to much useless expenditure of capital ; they have, however, never been extensive, have only been partial, and have never continued for any distance.

In some cases where the paddocks have been so situated that the co-party have had to tip the stripping upon their own land, they have been compelled to work the ground under these tips by tunnelling. It stands to reason that if they had to remove the earth tipped upon the land, as well as to strip from the surface down, the expense would be much too heavy for the yield of gold to sanction, and consequently they proceed by the more tedious method of tunnelling. This has to be done very cautiously, as, the whole being an alluvial deposit of decomposed granite, no distance can be driven with safety without securely propping and slabbing the top and sides of the drive. A movable framework is made by having two stout upright posts, one on each side, with even a stronger piece across from one to the other side capped in to the top ; this kind of frame is put in at every three or four feet, and the distance between is slabbed up, the ends of the slabs resting on the frame, and the top and side slabs supporting and blocking up each other ; this requires to be done with the greatest possible care, as the whole subsoil is so exceedingly treacherous, that as soon almost as put up, the earth comes down upon the slabbing and framework, and the weight it requires to bear up, is something enormous. Only a week or so ago, an accident occurred in one of the drives, by which the lives of three men were sacrificed. The drive was slabbed and propped, as it was thought securely, but owing to some cause that could not be explained, whether from the careless way of putting in the supports, or from some lateral or uneven pressure, one of the main side props gave way and then all the rest came down one by one like a card regiment. The depth of the cut was over, thirty feet and there was on this a tip of some sixteen or eighteen feet in height, and all this regularly caved in upon the poor fellows at work beneath it. I went into and inspected one of the drives in the immediate vicinity of where the accident occurred ; and, looking at the material that is worked into, and the nature of the soil ahead that has to be supported, it says much for the care and steadiness of the men that this should be the only accident that has happened. The drive I visited runs in for a distance of 100 feet, the boundary of the claim, and from this branch drives are driven in two or three places. There is a second drive put in, communicating by one of these branch galleries with the first or main drive, and thus causing not only a steady current of air, but also offering an outlet for escape in the event of a slip of earth behind the workmen. The wash dirt is a very coarse grit of decomposed, or rather abraded, granite, mixed with large stones, and full of water. Above this often lies a bed of stones mingled with the sand formed by the decomposed granite, from which also water drains in large quantities, causing a certain caving unless the drive be slabbed. The drives ore, of course, well drained down into a well, which is kept clear by the pumps attached to every paddock. The drive I am now speaking of is about four feet high, and a tram way is laid down in it, along which a small truck mounted on flange wheels is made to travel, bringing out the wash-dirt to the boxes at the opening of the drive. There were four men at work in the drive, two employed bringing out the wash-dirt, and three at the sluice-boxes. The boss or ganger was engaged in the interesting avocation of panning cut the gold, but his chief business was looking after the security of the slabbing of the drive. The tunnelling is a much longer and more troublesome way of getting out the gold than the stripping, and it is therefore only entered upon when the ground is doubtful, and by way of testing it, or when the ground above has been tipped upon. Some of these tips are very extensive, and are often as much as eighteen and twenty feet high. As the earth falls over from the carts at a regular angle, being very nearly the same as that adopted by military engineers in the construction of their earthworks, it requires but a very small sketch of fancy on the part of the beholder to make him imagine that he sees before him some vast defensive works in progress of construction and he may almost trace out bastions, ravelins, curtains, and fosses, crowned by some more lofty tips than usual to answer for the enceinte or inner line of works. I can tell you what my opinion is, after looking at this vast upheaval of soil, all caused by human hands, and after seeing the mass of earth that forty men and twenty horses and carts can, by working on a system, remove in a day ; it is this, that if American or Russian enemies visit Sydney, and a few hundred of our hardy diggers will only work with the same will in the defence of their native or adopted land, as they do in their search after the irritamenta malorum, four-and-twenty hours would see such works constructed as would puzzle even the Dahlgren guns of Uncle Sam, and make Brother Jonathan, wide-awake as he is, open his eyes ‘ considerable.’ Since I have seen Araluen, and have discovered what our men can do on a pinch, my mind has been very much easier on the subject of our defences.

An interesting snippet was found in the Sydney Mail22Sydney Mail, 29 July 1865. related to the horses used in the 1860s …

The amount of horse food required for Araluen alone is something enormous. The thirty claims working there employ on an average fourteen horses each, or 420 in all. These horses do an immense deal of very hard work, and require to be well fed, so that to supply these no small quantity of fodder is required. It is all sent from Braidwood, cut into chaff, and packed in wood bags, which, when the chaff is pressed into them, will hold from 4 cwt. to 5 cwt. each. Owing to this scarcity of feed, horses are selling at a mere nominal figure, and it is mentioned as a joke that a dealer went into a public-house for change for a pound note, because, as he said, he was going to buy three or four horses, and wanted to pay for them as they were knocked down to him.

Mail Deliveries

Mail deliveries were a problem experienced throughout the Araluen Valley. It is brought to our attention here by a miner from Bell’s Creek in 185323Goulburn Herald, 17 September 1853. …

To the Editor of the Goulburn Herald.

SIR,–It is a most grievous affair that we diggers upon the Araluen and Bell’s Creek are utterly deprived of the mail. Here we are a distance of from ten to fifteen miles from Braidwood, and are often obliged to be our own postmen to and from Braidwood. A contract has been made and entered into between a Mr. Pane and the Post Office authorities, to collect the mail between Braidwood and this place three times a week, and in no one instance has the contract been been fulfilled. Now, Sir, as the government taxes us heavily enough for those things we might reasonably expect to get our letters in due time. Whereas, if we do not fetch the mail ourselves, our letters are detained five or six days on their passage between Braidwood and this place. And in more than one instance to our own knowledge the mail bag has laid here for a whole week without this immaculate postman calling for it. Indeed the complaint is so general here especially among men who have families in Goulburn and elsewhere that we sincerely hope you will call the attention of Government to this gross neglect of public duty. Hoping you will insert this in your widely circulated journal. We remain, Sir, Your Humble Servants, PETER ROSS, Wm. WAKLEY, Bell’s Creek, August 31, 1853.

From the following it appears that mail contracts were for a two year period, then reviewed 24Goulburn Herald and County of Argyle Advertiser, 10 December 1853. …

Mr Rutledge’s tender for the mail between Goulburn and Braidwood has been accepted. We suppose that our old friend Mr. J. J. Roberts will ” horse” the line ; if so, those who travel the road will have no cause for dissatisfaction.

Then, in 1856 …

Mr. John Joseph Roberts, of the Goulburn Hotel, has undertaken to carry the mail from and to Goulburn, Boro, and Braidwood ; and from and to Boro, and Queanbeyan via Bungendore, thrice a week ; by a one horse vehicle, from and to Queanbeyan and Cooma twice a week ; and on horseback, from and to Braidwood, Bell’s Creek, Bell’s Paddock, and Major’s Creek, thrice a week, for £1195, and £1 10s. per seat for all places required by Government.These arrangements were renewed every 2 years.

By 1858 the price paid to mail contractors had risen to £1910. 25Goulburn Herald and County of Argyle Advertiser, 5 January 1856.

The Diggers Employment Committee

This committee was first mentioned in the newspapers in November 1858. The committee took applications from diggers outside NSW who were looking for help getting to the diggings in NSW. Most of the initial applicants were from Victoria with some from Rockhampton. Different numbers were sent to the various fields in NSW. Of the 1110 applicants in early November 1858, 150 were sent to the Braidwood and adjacent diggings 26Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, 6 November 1858..

Gold Sales

Initially there was no official arrangement for gold sales. Miners were in the habit of storing their gold in hidden places until there was enough to make the trip to Braidwood, where it could be sold. This could be a dangerous and time consuming trip due to the lack of a direct track, the steep slopes encountered, and the possibility of robbery. In 1859 the track out of the valley was to Braidwood via Major’s Creek 27Sydney Morning Herald, 25 August 1859. …

Active steps have been taken for the formation of a saddle-track down the Araluen Valley, from the Major’s Creek range. This undertaking, which will cost about £150, is to be performed by private subscriptions and with voluntary labour. Those who are not able to give cash give their labour gratis, and through this mutual and united undertaking of the inhabitants the path in question will be completed before a week.

By horseback this would be an eight hour return trip, but not all miners had horses. Once stores were built in the valley, some store keepers would buy gold and arrange for a private carrier to take the gold. John Blatchford was the main gold buyer and carrier in the 1850s and 1860s.

A separate Gold Escort for Araluen did not commence until 1867.

In 1853 the Maitland Mercury commented on the amount of gold sold in the Braidwood district 28Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, 3 September 1853. …

Two years have elapsed since we became a gold producing district. In that time I find the escort and mails have conveyed to Sydney from hence about 81,000 ounces of gold. I can account for some 30,000 ounces to be added to this, and no doubt, as a great deal still finds its way from the district privately, we should be fully justified in estimating the total amount at 150,000 ounces, which at £3 10s. will give £525,000 as the value of our two years work. It is certainly a significant fact, for which I confess I was not prepared, that more went down by escort during the first six months it was running than during the fifteen months that have since elapsed. (From the Goulburn Herald).

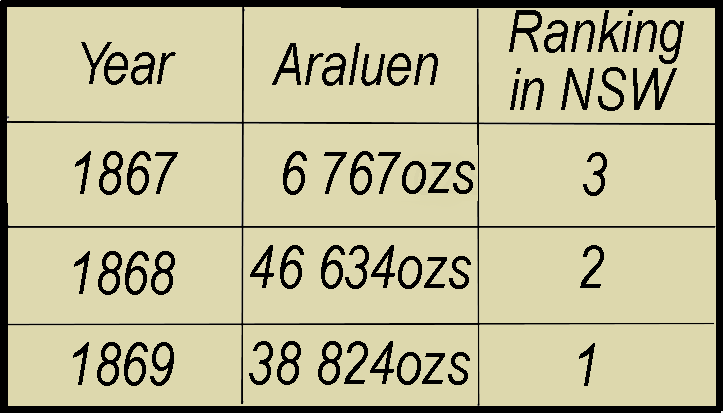

These are the official escort figures for this period of mining in Araluen 29McGowan, The Golden South, p 52. …

Dredging of the stream beds, did not start until the 1870s and reef mining of the gold bearing ore and gold processing did not start until the 1880s.

Information on each of the various mining areas in the Araluen Valley can be found in further articles on this site.